Introduction

“Inflation is everywhere and always a monetary phenomenon”

This famous quote by Milton Friedman in his classic book published in 1963 has, over the years, been misunderstood and wrongly interpreted. The full statement by Friedman and his co-author Anna Jacobson Schwartz in their book “A Monetary History of the United States” reads: “Inflation is everywhere and always a monetary phenomenon, resulting from and accompanied by a rise in the quantity of money relative to output.” Many are only familiar with the first part of the sentence, which suggests that inflation is always a result of monetary expansion. The second part, which stipulates the condition for this to hold, is less known. This, in turn, affects the understanding of the condition in which an increase in the quantity of money results in inflation. What the sentence as a whole implies is that monetary expansion is only inflationary to the degree that it results in a growth in demand beyond the prevailing level of output in the economy. It identifies increased demand pressures due to expansion in the quantity of money in the economy as the primary factor driving inflation.

The Transmission of Monetary Expansion is Divergent Across Economies

In most advanced economies like the United States, due to the highly developed structure of the financial market, monetary expansion is inflationary as it triggers an increase in the quantity of money in the economy, resulting in upward pressures on consumer demand beyond the growth in the prevailing level of output. The channel through which this occurs is straightforward. An increase in money supply in the economy triggers an expansion in consumer credit or an appreciation in the value of assets, which feeds into consumption growth as individuals and households increase their spending levels.

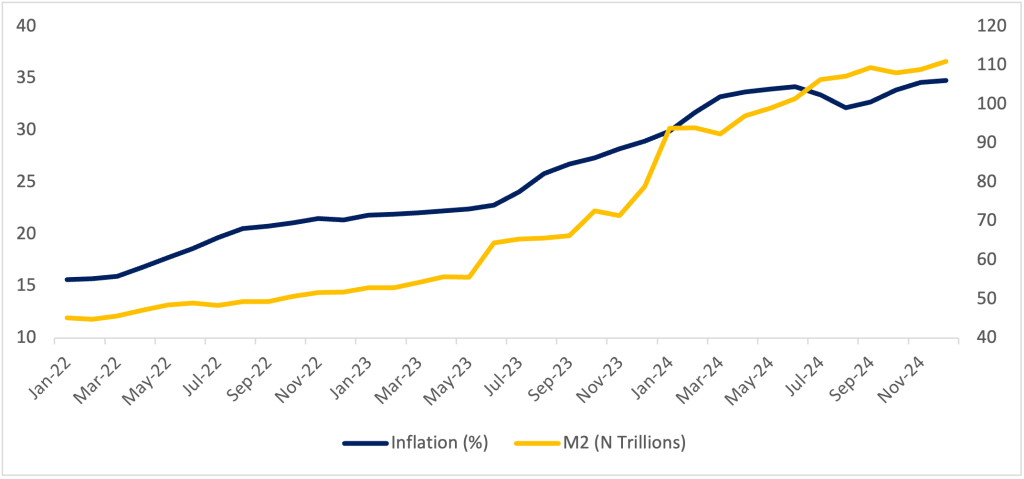

Figure 1: Trend of Inflation Rate and Money Supply (M2)

Source: Kingsgate Research, Data: CBN

This is obviously not the case in the context of the Nigerian economy. However, many do not understand why this conventional wisdom that largely explains the dynamics of price movements in many advanced economies does not hold for Nigeria. The graph above characterizes this puzzle. While it depicts a positive correlation between monetary expansion and inflation, basic economics and statistics teaches it does not necessarily imply that an increase in the quantity of money will be inflationary; in essence, correlation does not imply causation. As such, it is important to investigate the channel through which monetary expansion leads to inflation within the context of the Nigerian economy. This will provide deeper insight into the dynamics of the observed relationship. First, the financial system in Nigeria in its current form (due to the absence of a strong credit market) is not structured for monetary expansion to channel credit to the demand side of the economy; that is, to drive growth in consumption by households as is the case in an advanced economy like the United States. Instead, credit expansion in Nigeria funds government consumption much more than it does consumer demand. In recent years, fiscal financing by the monetary authority has resulted in the Ways and Means extended to the government soaring to unsustainable levels.

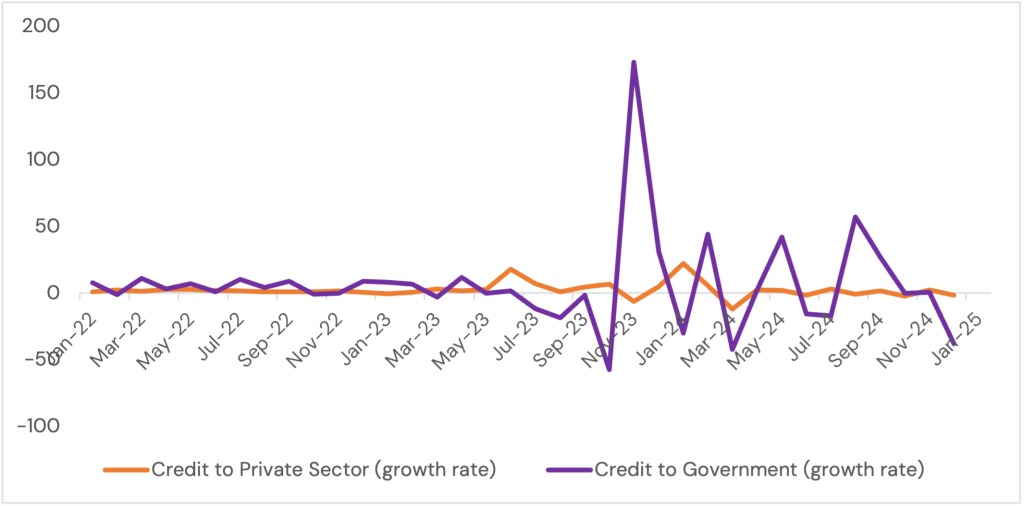

Figure 2: Credit to the Private and Public Sector (Growth Rate)

Source: Kingsgate Research, Data: CBN

Credit to the private sector, on the other hand, has been constrained due to the high-interest-rate environment. This has, in turn, inhibited business expansion, which is required to boost spending by households through higher wages and increased employment opportunities. Figure 2 shows that credit to the government has mostly grown at a faster rate than credit to the private sector.

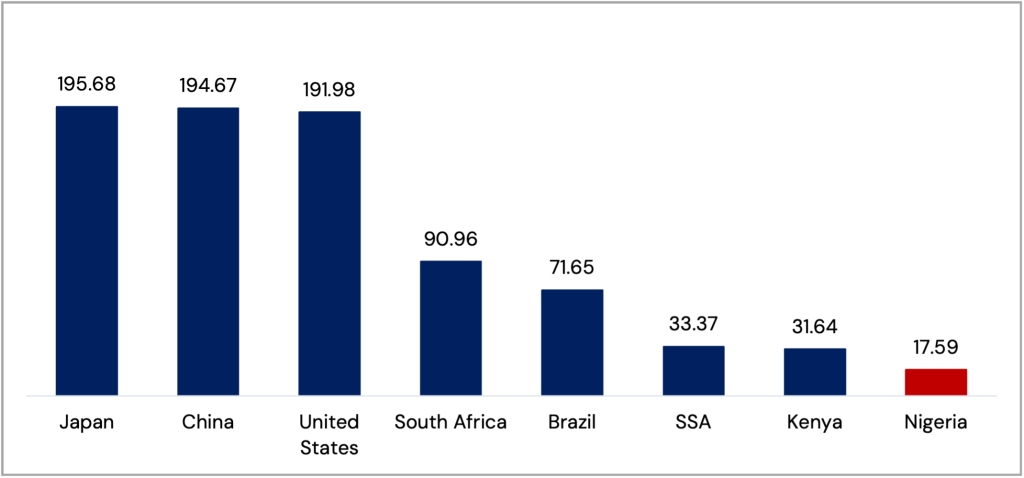

Second, unlike in China, where the financial system is structured to direct credit to boost supply-side activities and drive productivity growth without resulting in inflationary pressures in the economy, the financial system in Nigeria is not structured to channel credit (in a significant proportion) to boost productivity in the economy. Figure 3 shows that that the percentage of credit directed to the private sector (as at 2023) is very low in Nigeria (at 18%), below the Sub-Saharan African average (at 33.4%) and far lower than that of advanced and emerging market economies like China (194.7%), South Africa (91%) and Brazil (71.7%). In China for example, credit expansion is channeled through businesses, state-owned organizations and the government to fund supply-side activities such as infrastructure investment and manufacturing activities that boost productivity in the economy. This is why monetary expansion in China has not been inflationary.

Figure 3: Credit to Private sector (% GDP)

Source: Kingsgate Research, Data: World Bank

The Transmission of Monetary Expansion in Nigeria is Complicated by Several Factors

The unique context of the Nigerian economy raises a critical question relevant to understanding the transmission channel of monetary expansion in the economy as well as the design of a robust monetary policy strategy by the Central Bank. If monetary expansion does not have a significant impact on the demand-side of the economy by directing credit to drive growth in household consumption as is the case in a typical advanced economy like the United States and if it also does not also significantly affect the supply side of the economy by channeling credit to boost productive activities as is the case in an emerging market economy like China, does this imply that monetary expansion has no effect on inflation in Nigeria as is the view widely held by the public?

In Nigeria, the transmission channel of monetary expansion is complicated by several factors. Apart from the shallow financial market in the economy, the almost absent consumer credit market, and the financing of fiscal deficits through Ways and Means, the transmission channel of monetary expansion is convoluted majorly by the high level of informal dollarization in the economy, the high import dependence of the economy due to decades-long pre-existing weaknesses in domestic productivity levels, and years of accumulated policy errors by both the monetary and fiscal authorities.

Monetary Policy Transmission is Weak in Dollarized Economies

Dollarization (even though unofficial) has, over the years, been deeply entrenched in the Nigerian economy. Factors responsible for this include the uncontrolled expansion of the parallel market for the exchange rate, activities of foreign exchange speculators, and the portfolio allocation decision of individuals, investors and financial institutions to hedge against loss of value of the naira and the high inflationary environment. Research has shown that monetary policy transmission is weak in dollarized economies. The high degree of informal dollarization in the Nigerian economy is, therefore, a major reason monetary expansion does not translate into an increase in consumer demand in the economy. Instead of an increase in the quantity of money in the economy being channeled towards the expansion of business activities to increase wages and employment or towards the expansion of credit to consumers to boost consumption expenditure, the excess liquidity in the economy, held majorly by financial institutions, the government (federal and state) and few ultra-wealthy individuals typically mounts pressure on the exchange rate as demand for dollars surges in the economy. To underscore the pervasiveness of dollarization in the Nigerian economy, the first ever Domestic Dollar Bond of an initial offer of US$500 million was oversubscribed by US$400 million, with a total of US$900 million raised. Also, the monetary authority has, in recent times, observed a clear correlation between FAAC allocation to states and depreciation pressures on the exchange rate.

High Import Dependence and Accumulated Policy Errors Complicate the Situation

The high import dependence of the economy also weighs heavily on the exchange rate due to the demand for dollars to pay for imports. Accumulated policy errors over the years by the monetary and fiscal authorities have further complicated the situation. In recent times, this includes the excessive fiscal deficit financing by the Central Bank through ways and means advances to the government which reached unsustainable levels in 2023, years of excessive borrowing to defend the naira and to fund the budget deficit, poorly implemented development finance schemes by the Central Bank, and more recently, the lack of proper sequencing and coordination in undertaking important reforms such as the unification of the exchange rate windows, the floating of the naira, and the removal of fuel subsidies. The combined impact of shocks from these policy actions resulted in large-scale depreciation of the naira and a surge in inflation due to the pass-through effect of exchange rate depreciation on domestic prices.

Inflation is a “Wicked Problem”

From the foregoing, it is evident that monetary expansion does, in fact, negatively impact inflation in Nigeria, although through an indirect and complicated channel. Its effect on inflation occurs predominantly through the exchange rate channel and not through the credit channel, as is the case in many advanced economies. However, this channel is also convoluted by several factors, making it impractical to attribute all changes in inflation to the pass-through effect of exchange rate fluctuations on domestic prices. Apart from the factors previously identified, inflation also responds to supply chain and logistics complications, insecurity in the country, and external shocks such as oil price shocks, policy shocks from the U.S, and global shocks like the financial crisis and the pandemic. Inflation can therefore be referred to as a wicked problem – a problem with a complex network of interdependencies and is resistant to conventional and simple solutions.

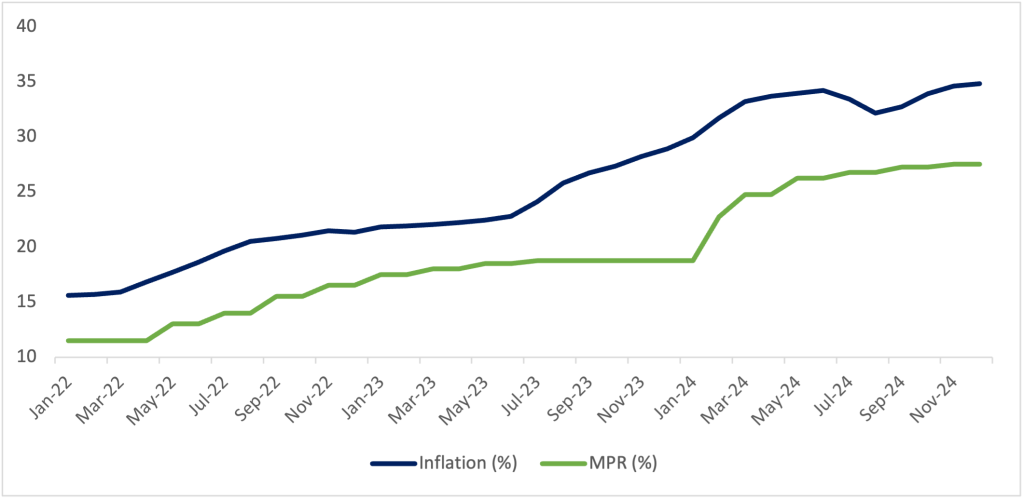

Figure 4: Trend of Inflation Rate and Monetary Policy Rate (MPR)

Source: Kingsgate Research, Data: CBN

As such, the problem of high inflation in Nigeria cannot be resolved by focusing on the credit channel through interest rate adjustments to vary the quantity of money in the economy, which has proved to be mostly counterproductive. Figure 4 reveals that despite rate hikes to unprecedented levels, inflation continued to trend upwards. The recent decline observed in the January 2025 data is due to the rebasing of the CPI basket. Moreover, focusing on the exchange rate channel alone under the current monetary policy framework of the Central Bank is not presently sustainable as it will require large-scale interventions in the foreign exchange market. Even if the CBN reverts to exchange rate targeting, as some have advocated for, the need for robust reserves to continually intervene against fluctuations in the exchange rate also raises concerns over its sustainability. For this policy framework to be effective, the Central Bank needs a large war chest of reserves, and to build reserves in the short run it needs to continue to attract both domestic and foreign investors by either raising interest rates (which is undesirable due to its negative effect on the real sector), maintaining the current rates (as it has recently done) or lowering it (which will not be attractive to investors).

Managing Trade-offs and Minimizing the Unintended Consequences of Policy Decisions

Managing several trade-offs and minimizing the unintended consequences of decisions creates a policy dilemma for the monetary authority as it pursues multiple objectives: ensuring price stability, managing capital flows to ensure reserves are robust and adequate to support foreign exchange intervention and cover for imports, and boosting productivity in the economy to prevent the further contraction of the real sector. It is in the effective coordination of these multiple objectives (by using multiple tools) that some meaningful gains can be recorded in the quest towards inflation reduction, at least from the monetary policy perspective. Focusing on a single objective will be counterproductive. In observing the behaviour of the monetary authority in recent times, while it has communicated price stability as its major focus, it has in fact, pursued multiple objectives, including price stability, exchange rate stability, and the management of capital flows by combining multiple tools such as the Monetary Policy Rate (MPR), Open Market Operations (OMO), the Cash Reserve Ratio (CRR), Foreign Exchange Intervention (FXI) and Macro Prudential Policy.

The Need for a Rethink of the Current Monetary Policy Framework of the Central Bank

The policy framework adopted by the monetary authority also has an important role to play. While not yet in full adoption, the Central Bank has signaled its intention of transitioning to an inflation-targeting policy framework. If we assume this framework will eventually be adopted, it is critical to consider how it should be effectively applied to rein in inflation. Studies have shown that in practice, policy makers of developing countries that adopt inflation targeting have mostly defied the conventional wisdom of out rightly floating their exchange rate. The studies reveal that for less developed countries (LDCs), inflation targeting is only effective if the monetary authority also adopts an exchange rate management policy (such as a crawling peg or a tightly managed float) to mitigate fluctuations in the exchange rate. This requires the coordination of two major instruments: the interest rate to anchor prices and foreign exchange intervention to anchor exchange rate fluctuations. In Nigeria, due to the weak transmission of monetary policy, other instruments besides these two would have to be adopted. Moreover, even though the Central Bank has been intervening in the foreign exchange market to mitigate fluctuations in the exchange rate, adopting a tightly managed float or crawling peg will ensure its activities are better sequenced and effectively coordinated. Another article will provide an in-depth and nuanced analysis of the most appropriate monetary policy framework for the Central Bank, given the unique context of the Nigerian economy.

Conclusion

This article has examined the question of whether inflation in Nigeria is a monetary phenomenon. It has shown that while the transmission of monetary expansion in Nigeria is convoluted by several factors, inflation in Nigeria does have some roots in monetary expansion. It then proceeded to argue that controlling inflation from a monetary policy perspective would require the coordination of multiple objectives by the monetary authority using multiple tools, as well as the adoption of an appropriate monetary policy framework. It is, however, important to note that considering the complicated nature of inflation in Nigeria, monetary policy alone at its best, even if it coordinates its objectives using the required tools in the most effective manner, cannot fully control inflation. Taming inflation in Nigeria will require the effective coordination of several policies beyond monetary policy, including fiscal policy, trade policy, investment policy, industrial policy and other relevant policies to ensure macroeconomic stability and boost productivity in the economy. It will also involve dealing with insecurity that has undermined agricultural productivity, business expansion and foreign direct investment inflow. An in-depth discussion of how the different policies should be effectively coordinated to drastically rein in inflation is beyond the scope of this article. Another article will examine it.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of Kingsgate Advisors Institute or the Nigerian Economic Summit Group or their Board of Directors.